If you’re searching for TypeScript interview questions and answers, you probably want two things: direct interview-ready responses and practical examples that compile. This guide is built for exactly that covering beginner through architect level, plus a TypeScript coding interview practice set and a compiler-error debug section. You’ll also see real-world common mistakes about tsconfig, module interop, narrowing, and generics (yes, including TS generics interview questions). Use it as TypeScript interview prep, or as a quick refresher the night before your TypeScript coding interview.

Who this guide is for:

- Freshers who want confident fundamentals with examples that compile

- Mid-level devs who want to close gaps on

tsconfig, modules, and utility types - Seniors/architects who want deep typing + real production tradeoffs

How to use this guide:

- Read the Short answer out loud (that’s your interview response)

- Paste snippets into a scratch file and run

tscto feel the rules - After each level, do the coding tasks and the compiler-error drills

Table of Contents

Quick roadmap (study order)

- Start with the basics: what TS is, compilation, structural typing, unions + narrowing

- Then lock in: functions (overloads/generics), interfaces vs types, utility types

- Next:

tsconfigoptions that change safety + behavior (strict family, module settings) - After that: advanced typing (mapped/conditional types,

infer, template literals,satisfies,as const) - Finally: real-world scale (declaration files, augmentation, Result patterns, build performance)

- Practice loop: read → code → debug → repeat (TypeScript interview questions get easy when you iterate)

TypeScript interview questions and answers

What is TypeScript?

Short answer: TypeScript is JavaScript with a compile-time type system that helps you catch mistakes before running your code.

Deeper explanation: Think of TS as a very smart spellchecker for your code. It reads your .ts files, checks types, and emits plain JavaScript. Types improve safety, refactoring, and autocomplete, but they don’t exist at runtime. So TS prevents whole classes of bugs, but you still need runtime checks for untrusted data.

function greet(name: string) {

return `Hi ${name.toUpperCase()}`;

}

console.log(greet("Ada"));

Behavior/output: Prints Hi ADA. Types are erased when compiled.

Common mistake: Believing TS “enforces” types at runtime-only JavaScript runs at runtime.

TypeScript vs JavaScript: what’s the real difference?

Short answer: TypeScript adds static typing and tooling; JavaScript is dynamically typed and runs directly in the runtime.

Deeper explanation: JS lets you do anything and fail later; TS tries to fail earlier (at compile time). TS still outputs JS, so runtime behavior comes from emitted JS, not types. In interviews, a clean line is: “TypeScript improves correctness and developer experience without changing the underlying runtime.”

// JS would allow this until runtime:

function add(a: number, b: number) {

return a + b;

}

// add("1", 2) // compile error in TS

Behavior/output: TS blocks incorrect calls before you run code.

Common mistake: Saying “TypeScript is a different language runtime.” It’s a superset that compiles to JS.

What does “TypeScript compiles to JavaScript” mean?

Short answer: tsc transforms TS syntax into JS and removes type annotations completely.

Deeper explanation: Compilation is mostly “erase types + adjust syntax” based on target and module. You can also generate .d.ts files for consumers. But no matter what, types do not ship to the JS engine.

const add = (a: number, b: number) => a + b;

console.log(add(2, 3));

Behavior/output: Prints 5; the emitted JS won’t contain : number.

Common mistake: Expecting TS types to prevent undefined property access at runtime without checks.

What is type checking?

Short answer: It’s the compiler verifying that values are used consistently with their types.

Deeper explanation: TS checks assignments, function calls, property access, and control flow. It also uses inference to figure out types when you don’t annotate. Type checking is why TS catches “typos with confidence” (like wrong property names) before you ship.

let x = 1;

// x = "oops"; // error

Behavior/output: Compile-time error stops the mismatch.

Common mistake: Over-annotating everything instead of letting inference help.

What is structural typing?

Short answer: Compatibility is based on “shape” (properties), not the declared name of the type.

Deeper explanation: If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, TS treats it like a duck. That’s why plain objects are so ergonomic. But it also means different domain concepts can become accidentally compatible if they share the same structure.

type Point = { x: number; y: number };

type Coords = { x: number; y: number };

const p: Point = { x: 1, y: 2 };

const c: Coords = p; // OK

Behavior/output: Assignment works because shapes match.

Common mistake: Expecting nominal typing (where names matter) like in some other languages.

Interview tip: Start answers with a one-liner, then add one real implication (“types are erased,” “shape-based,” “needs narrowing”).

What are TypeScript primitive types?

Short answer: string, number, boolean, bigint, symbol, null, undefined.

Deeper explanation: These represent JavaScript primitives plus explicit typing for null/undefined. With strictNullChecks, null and undefined become very important because they’re not assignable to most types unless you include them.

let s: string = "ok";

let n: number = 42;

let b: boolean = true;

Behavior/output: All are plain JS primitives at runtime.

Common mistake: Treating null as assignable everywhere (not true with strict null checking).

What is type inference?

Short answer: TS automatically figures out types from values and usage.

Deeper explanation: Inference keeps code clean: you don’t annotate everything. But inference can widen types if something is mutable (like let). When you want literal precision, use as const or satisfies.

const a = "GET"; // inferred as "GET"

let b = "GET"; // inferred as string (widened)

Behavior/output: const preserves literal type; let usually widens.

Common mistake: Assuming mutable variables keep literal types.

What are union types?

Short answer: A union A | B means a value can be either A or B.

Deeper explanation: Unions model real-world “either/or” data: string | null, success-or-error shapes, and more. To use a union safely, you narrow it first with checks like typeof, in, or discriminants.

function printId(id: string | number) {

if (typeof id === "string") return id.toUpperCase();

return id.toFixed(2);

}

console.log(printId(12.3));

Behavior/output: Prints 12.30 for number input.

Common mistake: Accessing members that exist only on one side of the union without narrowing.

What are intersection types?

Short answer: An intersection A & B combines types; values must satisfy both.

Deeper explanation: Intersections are great for composing object capabilities (like “has id” + “has timestamp”). Watch for conflicting property types-those can produce impossible types.

type HasId = { id: string };

type HasName = { name: string };

type User = HasId & HasName;

const u: User = { id: "u1", name: "Ada" };

console.log(u.name);

Behavior/output: Prints Ada.

Common mistake: Intersecting incompatible properties (e.g., {x: string} & {x: number}).

What are literal types?

Short answer: Literal types restrict values to exact literals like "GET" or 42.

Deeper explanation: They’re perfect for “allowed values” and discriminated unions. Without help, TS may widen literals into string/number, so preserve literals with as const or satisfies when needed.

type Method = "GET" | "POST";

const m: Method = "GET";

// const bad: Method = "PUT"; // error

Behavior/output: Compile-time restriction to allowed strings.

Common mistake: Losing literal types by annotating too broadly (const m: string = "GET").

Interview tip: When unions show up, say “narrowing” early-interviewers want to hear you know how to use unions safely.

What are tuples?

Short answer: Tuples are fixed-length arrays with known types at specific positions.

Deeper explanation: Use tuples for structured pairs like [value, error] or coordinates [x, y]. They’re more precise than any[] and often cleaner than small objects when order matters.

const pair: [number, string] = [200, "OK"];

console.log(pair[1].toUpperCase());

Behavior/output: Prints OK.

Common mistake: Treating tuples as unlimited arrays (pushing extra values can lead to weak guarantees).

What are enums, and what’s a safer alternative?

Short answer: Enums create named constants but can introduce runtime output; literal unions are often safer.

Deeper explanation: Numeric enums generate runtime objects and reverse mappings, which can surprise you and add bundle weight. For many use cases, "a" | "b" unions plus as const are simpler and more predictable.

enum Status { Idle, Loading, Done }

const s = Status.Loading;

console.log(s);

Behavior/output: Prints 1 (numeric enum).

Common mistake: Assuming enums are type-only. They emit JavaScript.

What is any?

Short answer: any turns off type checking for that value.

Deeper explanation: any is contagious: it spreads through your code and deletes safety. It can be useful during migrations, but in clean TS, prefer unknown and narrow.

let v: any = 123;

v.toUpperCase(); // compiles, but can crash at runtime

Behavior/output: Runtime error: toUpperCase is not a function.

Common mistake: Using any to “fix” errors instead of modeling types.

What is unknown?

Short answer: unknown means “I don’t know yet,” and you must narrow before using it.

Deeper explanation: This is your best friend at boundaries (JSON, env, network). You can assign anything to unknown, but you can’t touch it until you prove what it is. That forces safe code.

function upperIfString(x: unknown) {

if (typeof x === "string") return x.toUpperCase();

return "not a string";

}

console.log(upperIfString("hi"));

Behavior/output: Prints HI.

Common mistake: Casting unknown to a type without a runtime check.

What are never and void?

Short answer: never means “cannot happen” (no value ever); void means “no useful return value.”

Deeper explanation: A never function always throws or never finishes; void functions can still return undefined. never is also used for exhaustiveness checks in unions.

function fail(msg: string): never { throw new Error(msg); }

function log(msg: string): void { console.log(msg); }

Behavior/output: fail throws; log prints and returns undefined.

Common mistake: Using void when you mean “this never returns” (use never).

Interview tip: If asked

anyvsunknown, your winning line is: “unknownforces narrowing, so it’s safer.”

Compare any vs unknown vs never vs void

Short answer: any disables safety, unknown requires proof, never is impossible, void is no meaningful return.

Deeper explanation: Interviewers love this because it shows you understand boundaries and correctness. Use unknown at boundaries, use never for exhaustiveness, and use void for side-effect functions.

| Type | Meaning | Safe by default? |

|---|---|---|

any |

“trust me” | No |

unknown |

“untrusted” | Yes |

never |

“impossible” | Yes |

void |

“no useful return” | Yes |

type A = unknown;

type B = any;

Behavior/output: Purely compile-time; no runtime change.

Common mistake: Treating unknown like any and skipping narrowing.

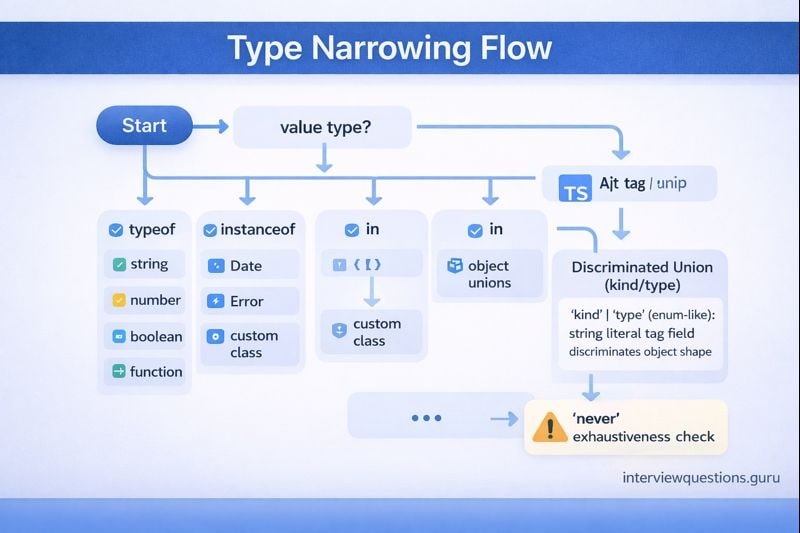

How do you narrow types with typeof?

Short answer: Use typeof for primitive checks to pick the correct branch safely.

Deeper explanation: typeof works for strings, numbers, booleans, functions, etc. Be careful with objects: typeof null === "object", so check x !== null too.

function fmt(x: string | number) {

return typeof x === "string" ? x.toUpperCase() : x.toFixed(1);

}

console.log(fmt(1.23));

Behavior/output: Prints 1.2.

Common mistake: Using typeof x === "object" and forgetting null.

How do you narrow with instanceof?

Short answer: instanceof narrows values created by constructors (like Date or custom classes).

Deeper explanation: This is runtime-based narrowing and works great with classes. It does not apply to interfaces because interfaces don’t exist at runtime.

function show(x: Date | string) {

if (x instanceof Date) return x.toISOString();

return x.toUpperCase();

}

console.log(show("hi"));

Behavior/output: Prints HI.

Common mistake: Expecting instanceof to work for interface types.

How does the in operator help narrowing?

Short answer: "prop" in obj checks if a property exists and narrows unions of object shapes.

Deeper explanation: It’s very useful when union members differ by fields. Like {"type":"a", a:...} vs {"type":"b", b:...}-though discriminants are even cleaner. Guard against null first.

type A = { a: number } | { b: string };

function f(x: A) {

if ("a" in x) return x.a;

return x.b.length;

}

console.log(f({ b: "hey" }));

Behavior/output: Prints 3.

Common mistake: Using in on values that might be null/undefined.

What is a discriminated union?

Short answer: It’s a union with a shared literal field (like kind) that makes narrowing reliable.

Deeper explanation: This is one of the most “ship-ready” TS patterns. It models states and results clearly, and it scales as your app grows. Pair it with exhaustiveness checks to force handling when you add a new case.

type Result = { ok: true; value: number } | { ok: false; error: string };

function handle(r: Result) {

return r.ok ? r.value : `Error: ${r.error}`;

}

console.log(handle({ ok: true, value: 7 }));

Behavior/output: Prints 7.

Common mistake: Using ok: boolean instead of ok: true | false literals, which weakens narrowing.

Interview tip: Discriminated unions +

neverexhaustiveness is a “senior signal.” Mention it naturally.

What is a type assertion (as)?

Short answer: A type assertion tells TS to treat a value as a type-without changing runtime behavior.

Deeper explanation: Assertions are okay when you’ve already validated something but TS can’t see it. They’re dangerous when used to silence errors. A good rule: assert only after a runtime check or at a trusted boundary.

const raw: unknown = "hello";

const s = raw as string; // unsafe unless you checked

console.log(s.toUpperCase());

Behavior/output: Works here, but can crash if raw isn’t a string.

Common mistake: Using assertions as a substitute for real validation.

When should you avoid type assertions?

Short answer: Avoid them when they bypass uncertainty-prefer narrowing or runtime checks.

Deeper explanation: If you’re dealing with unknown, external data, or optional values, assertions can turn into runtime crashes. Instead, validate and narrow. If you must assert, keep it local and justified.

function isString(x: unknown): x is string {

return typeof x === "string";

}

const v: unknown = "hi";

if (isString(v)) console.log(v.toUpperCase());

Behavior/output: Safe uppercasing after proof.

Common mistake: Writing v as string without checking typeof v.

What is optional chaining (?.)?

Short answer: It safely accesses properties/calls only when the left side isn’t null/undefined.

Deeper explanation: Optional chaining prevents “Cannot read properties of undefined” crashes. It’s especially useful with optional fields in strict mode. Combine it with ?? to provide defaults.

type User = { profile?: { email?: string } };

const u: User = {};

console.log(u.profile?.email ?? "unknown");

Behavior/output: Prints unknown.

Common mistake: Confusing ?. with falsy checks-?. only guards nullish values.

What is nullish coalescing (??)?

Short answer: a ?? b uses b only when a is null or undefined.

Deeper explanation: Unlike ||, it won’t replace valid falsy values like 0 or "". It’s perfect for defaults when 0 is meaningful.

function withDefault(x: number | undefined) {

return x ?? 10;

}

console.log(withDefault(0));

Behavior/output: Prints 0 (not 10).

Common mistake: Using || and accidentally overriding valid falsy values.

What are interfaces vs type aliases (beginner view)?

Short answer: Both describe shapes, but type is more flexible (unions), and interface supports merging and extension patterns.

Deeper explanation: If you’re defining a public object contract, interface can be nice. If you need unions, intersections, conditional types, or mapped types, you’ll use type. In many cases either works-choose a consistent style for your team.

interface IUser { id: string }

type Id = string | number;

Behavior/output: Types only; nothing emitted at runtime.

Common mistake: Thinking interface can directly express unions (it can’t).

Interview tip: For interface vs type, give a simple rule: “interfaces for object contracts, types for composition/unions.”

How do you type functions (params + return)?

Short answer: Annotate parameters and return types to lock in intent and prevent incorrect usage.

Deeper explanation: TS can infer return types, but explicit return types are great for public APIs. For small helpers, inference is usually enough. Balance readability with safety.

function sum(a: number, b: number): number {

return a + b;

}

console.log(sum(2, 3));

Behavior/output: Prints 5.

Common mistake: Leaving parameters untyped and accidentally getting any in non-strict configs.

What are optional parameters and default parameters?

Short answer: Optional params x?: T may be omitted; defaults provide a value when undefined is passed.

Deeper explanation: Optional means the type is effectively T | undefined in strict mode, so you must handle undefined. Defaults are often cleaner because they remove undefined inside the function.

function greet(name: string = "there") {

return `Hi, ${name}`;

}

console.log(greet());

Behavior/output: Prints Hi, there.

Common mistake: Using optional params and then forgetting they can be undefined.

What are rest parameters?

Short answer: Rest parameters gather remaining args into an array with a defined element type.

Deeper explanation: This is great for variadic functions. Keep rest types specific (avoid any[]). Later, you can make them tuples for even more precision.

function join(sep: string, ...parts: string[]) {

return parts.join(sep);

}

console.log(join("-", "a", "b", "c"));

Behavior/output: Prints a-b-c.

Common mistake: Typing rest as any[] and losing safety.

What is an index signature?

Short answer: It types objects accessed by dynamic keys: { [key: string]: T }.

Deeper explanation: Index signatures are useful for “dictionary” objects. But they imply all properties match the value type, which can be surprising. If keys are known, prefer Record<UnionKeys, V>.

type Scores = { [name: string]: number };

const scores: Scores = { ada: 10 };

console.log(scores["bob"] ?? 0);

Behavior/output: Prints 0 if missing.

Common mistake: Forgetting missing keys are undefined at runtime (even if the type says number).

What is Record<K, V>?

Short answer: It creates an object type with keys K and values V.

Deeper explanation: Record shines when K is a union of literals because TS enforces completeness. It’s a clean way to model lookup tables and configuration maps.

type Role = "admin" | "user";

const perms: Record<Role, string[]> = {

admin: ["read", "write"],

user: ["read"],

};

console.log(perms.admin.join(","));

Behavior/output: Prints read,write.

Common mistake: Using Record<string, V> when keys are actually optional-consider Partial<Record<K, V>>.

Interview tip: Show you think about runtime: “maps can miss keys, so I default or check.”

What does as const do?

Short answer: It preserves literal types and makes object/array literals readonly.

Deeper explanation: Without as const, TS often widens values (like "GET" → string). With it, TS keeps the exact values and prevents mutation, which is great for discriminants and lookup maps.

const cfg = { mode: "dev", retries: 3 } as const;

// cfg.mode is "dev"

console.log(cfg.mode);

Behavior/output: Prints dev.

Common mistake: Using as const and then trying to mutate the object later.

What is the satisfies operator?

Short answer: It checks a value matches a type without changing the value’s inferred type.

Deeper explanation: This is the sweet spot for configs: you get validation plus preserved literals. It avoids the “I annotated it and now I lost my literal types” problem.

type Config = { mode: "dev" | "prod"; retries: number };

const cfg = { mode: "dev", retries: 3 } satisfies Config;

console.log(cfg.mode);

Behavior/output: Prints dev; cfg.mode stays literal-friendly.

Common mistake: Using : Config and widening mode to "dev" | "prod" when you wanted "dev".

What is excess property checking?

Short answer: TS rejects extra properties on object literals assigned to a target type to catch typos.

Deeper explanation: This check applies strongly to object literals (“fresh” objects). If you assign the literal to a variable first, the extra-property check can behave differently because structural typing kicks in. It’s a classic interview trap.

type User = { id: string };

const u1: User = { id: "1", extra: 123 }; // error

const tmp = { id: "1", extra: 123 };

const u2: User = tmp; // OK

console.log(u2.id);

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Assuming TS always blocks extra props in all contexts.

What is exhaustiveness checking with never?

Short answer: It forces TS to error if you miss a case in a union handler.

Deeper explanation: This is how you make future refactors safe. Add a default branch that assigns to never. If someone adds a new union member and forgets to handle it, the compiler catches it immediately.

type Mode = "dev" | "prod";

function run(m: Mode) {

switch (m) {

case "dev": return 1;

case "prod": return 2;

default: {

const _x: never = m;

return _x;

}

}

}

console.log(run("dev"));

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Adding a default: return ... without a never check (future cases slip through).

Runtime vs compile-time: why do types “disappear”?

Short answer: Types are erased during compilation, so runtime is just JavaScript.

Deeper explanation: This is the boundary truth of TS. If you parse JSON or read environment variables, TS can’t magically guarantee the shape-your code must validate. The safe pattern is: treat input as unknown, validate, then narrow.

function parseJson(input: string): unknown {

return JSON.parse(input);

}

const data = parseJson('{"x":1}');

console.log(typeof data);

Behavior/output: Prints object. TS still treats it as unknown unless you validate.

Common mistake: Trusting JSON.parse() as if it returns a typed object.

Interview tip: If you say “types are erased,” follow with: “so untrusted inputs must be validated at runtime.”

Intermediate TypeScript interview questions and answers

What does strict: true do?

Short answer: It turns on a bundle of strictness checks for safer, more predictable typing.

Deeper explanation: strict enables things like noImplicitAny and strictNullChecks, which are huge for catching bugs early. In real projects, strict is the default you want, then you fix issues rather than turning it off.

let s: string = "ok";

// s = null; // error with strictNullChecks

console.log(s);

Behavior/output: Prints ok.

Common mistake: Disabling strict globally instead of dealing with a few hotspots.

What is noImplicitAny?

Short answer: It errors when TS would otherwise infer any for something.

Deeper explanation: This prevents “silent any” from quietly weakening your codebase. It’s especially valuable for function parameters. If you hit this error, add types or refactor to get inference working.

// function f(x) { return x; } // error with noImplicitAny

function f<T>(x: T) { return x; }

console.log(f(123));

Behavior/output: Prints 123.

Common mistake: “Fixing” it by writing x: any (you just hid the problem).

What is strictNullChecks?

Short answer: It makes null and undefined explicit, so you handle missing values safely.

Deeper explanation: With strict nulls, string is not string | undefined. That’s annoying for 10 minutes and life-saving for years. You’ll use optional chaining, defaults, and early throws more often.

function upper(x: string | undefined) {

return x?.toUpperCase() ?? "N/A";

}

console.log(upper(undefined));

Behavior/output: Prints N/A.

Common mistake: Spamming ! non-null assertions instead of modeling/handling undefined.

What does noUncheckedIndexedAccess do?

Short answer: It makes obj[key] return T | undefined, reflecting missing keys at runtime.

Deeper explanation: This is “reality mode.” Dictionaries and arrays can be out-of-bounds or missing keys. This option forces you to check or default, which prevents tons of production bugs.

const xs = [10, 20];

const v = xs[5]; // number | undefined

console.log(v ?? 0);

Behavior/output: Prints 0.

Common mistake: Disabling the flag because it “adds errors” instead of handling the real missing case.

What is isolatedModules?

Short answer: It ensures each file can be safely transpiled independently (important for per-file toolchains).

Deeper explanation: Some build pipelines don’t do full-program type transforms while transpiling. isolatedModules catches patterns that rely on cross-file type info. It reduces surprises when swapping compilers/transpilers.

export const x = 1; // simple module-friendly code

Behavior/output: Safe in isolated compilation.

Common mistake: Using patterns that require full type information during emit and then wondering why a toolchain breaks.

Interview tip: For

tsconfigflags, tie each one to a real bug it prevents. That’s what makes your answer memorable.

target: what does it change?

Short answer: It controls what JS syntax level TS emits (older vs newer JavaScript).

Deeper explanation: A lower target downlevels modern syntax for older runtimes; a higher target emits modern JS, usually smaller and faster. Choose based on your runtime environment, not vibes.

async function f() { return 1; }

f().then(console.log);

Behavior/output: Prints 1; emitted JS differs based on target.

Common mistake: Targeting too low and accidentally inflating output with helpers.

module: ES modules vs CommonJS?

Short answer: It controls whether TS emits import/export (ESM) or require/module.exports (CJS).

Deeper explanation: If your runtime expects ESM but TS emits CJS (or vice versa), you get confusing import errors. Decide your module format per package and keep it consistent.

export const answer = 42;

Behavior/output: Emission style depends on module.

Common mistake: Mixing module systems without understanding default import behavior.

What does moduleResolution do?

Short answer: It decides how TS finds modules for import statements.

Deeper explanation: It affects how TS interprets package exports, extensions, and lookup rules. If module resolution doesn’t match your runtime/bundler rules, you get “Cannot find module” in TS while runtime works (or the other way around).

import type { Answer } from "./types";

export {};

Behavior/output: Type-only import should resolve without emitting runtime code.

Common mistake: Changing module resolution strategy without aligning the ecosystem expectations.

What is esModuleInterop?

Short answer: It improves compatibility when importing CommonJS modules using ES import syntax.

Deeper explanation: Many CommonJS libraries don’t have true default exports, but developers write default imports anyway. This flag smooths that interop and reduces “default is undefined” runtime surprises.

// Example pattern: namespace import is always safe for CJS shapes

import * as path from "node:path";

console.log(path.sep);

Behavior/output: Prints your platform path separator.

Common mistake: Flipping this flag mid-project and breaking existing import styles.

What is resolveJsonModule?

Short answer: It lets you import .json files as modules with inferred types.

Deeper explanation: Great for config and static data. But remember: imported JSON is still runtime data from a file-safe-ish, but it can change. For external JSON inputs, still validate.

// Requires "resolveJsonModule": true in tsconfig

export {};

Behavior/output: This snippet is a placeholder; the key is the compiler option behavior.

Common mistake: Assuming JSON imports replace the need for runtime validation of external data.

Interview tip: Module questions are half TS, half runtime reality. If you say “it compiles,” also mention “it must run.”

What is noImplicitAny vs writing : any?

Short answer: noImplicitAny prevents accidental any; writing : any is a deliberate escape hatch.

Deeper explanation: In interviews, say you avoid any in application logic. If you must use it, isolate it at boundaries and immediately convert to unknown + validate.

function unsafe(x: any) {

return x.foo; // no safety

}

Behavior/output: Can crash if x doesn’t have foo.

Common mistake: Leaving any in shared utilities where it spreads everywhere.

How do type-only imports/exports help?

Short answer: They prevent runtime imports when you only need types, reducing side effects and cycles.

Deeper explanation: This matters in large codebases where imports can trigger module initialization. It also keeps emitted JS smaller and avoids “why is this module running?” surprises.

import type { User } from "./types";

export type { User };

Behavior/output: No runtime import emitted for the type-only import.

Common mistake: Importing a module just for types and accidentally executing its side effects.

What are function overloads?

Short answer: Overloads define multiple call signatures for one implementation.

Deeper explanation: Use overloads when return types depend on input types. Write several overload signatures, then one implementation that handles all cases.

function parse(x: string): number;

function parse(x: number): string;

function parse(x: string | number) {

return typeof x === "string" ? Number(x) : String(x);

}

console.log(parse("42") + 1);

Behavior/output: Prints 43 because parse("42") is a number.

Common mistake: Making the implementation signature too narrow (it must accept all overload inputs).

What are generic constraints (extends)?

Short answer: They restrict a generic type parameter to values with a required shape.

Deeper explanation: Constraints are how you safely access properties on a generic. They also help TS inference stay meaningful (instead of becoming too broad).

function getId<T extends { id: string }>(x: T) {

return x.id;

}

console.log(getId({ id: "u1", name: "Ada" }));

Behavior/output: Prints u1.

Common mistake: Over-constraining generics and making the function hard to reuse.

What are default type parameters?

Short answer: They provide a default type for a generic when none is inferred/provided.

Deeper explanation: Defaults make APIs friendlier. They keep the simple case simple while allowing advanced customization.

type Box<T = string> = { value: T };

const a: Box = { value: "hi" };

const b: Box<number> = { value: 123 };

console.log(a.value, b.value);

Behavior/output: Prints hi 123.

Common mistake: Putting defaults in the wrong position and breaking inference.

Interview tip: When generics show up, say “I use generics to preserve relationships between inputs and outputs.”

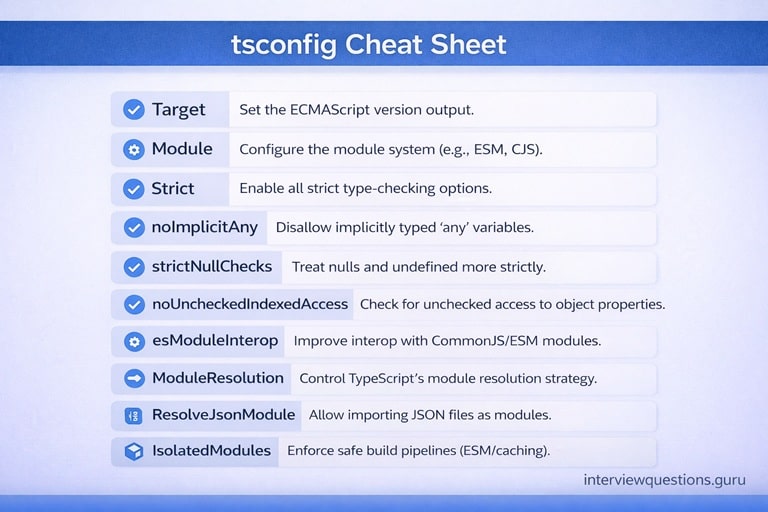

tsconfig cheat sheet

A compact cheat sheet that answers common tsconfig interview questions fast:

target: emitted JS syntax levelmodule: emitted module format (CJS vs ESM) If your interviews are backend-leaning, pair this with: [Node.js Interview Questions & Answer]strict: turns on strict bundlenoImplicitAny: blocks implicitanystrictNullChecks: null/undefined must be handlednoUncheckedIndexedAccess: indexed access becomesT | undefinedesModuleInterop: smoother CJS default import interopmoduleResolution: import resolution strategyresolveJsonModule: allow JSON importsisolatedModules: per-file transpile compatibility

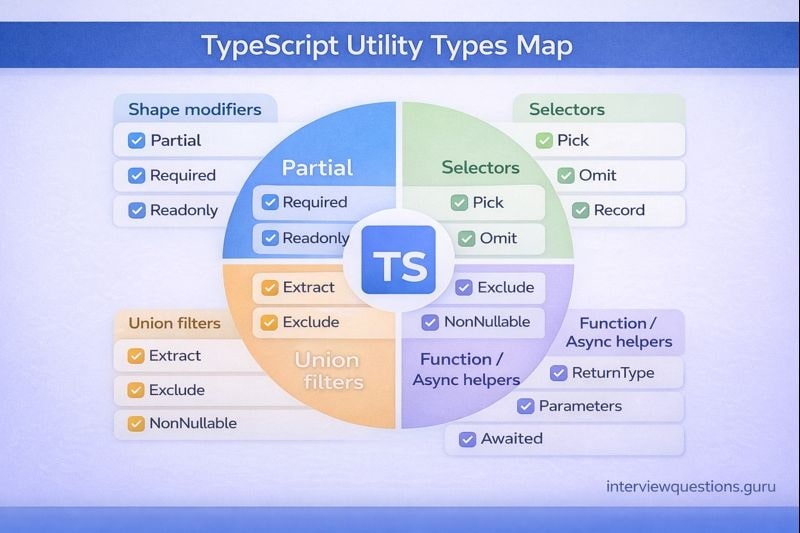

What are utility types (and which ones matter most)?

Short answer: Utility types transform existing types-like Partial, Pick, and Record.

Deeper explanation: They save you from rewriting the same shapes. The “core set” you should confidently explain: Partial, Required, Readonly, Pick, Omit, Record. Then mention you also know Extract, Exclude, NonNullable, ReturnType, Parameters, Awaited.

type User = { id: string; name: string; age?: number };

type Patch = Partial<User>;

type Preview = Pick<User, "id" | "name">;

Behavior/output: Compile-time transformations only.

Common mistake: Using Partial for updates without validating allowed fields.

ReturnType and Parameters: what do they do?

Short answer: They extract a function’s return type and parameter tuple types.

Deeper explanation: Great for wrappers and higher-order utilities so you don’t duplicate signatures. If the function changes, your wrapper’s types update automatically.

function makeUser(id: string, name: string) {

return { id, name } as const;

}

type P = Parameters<typeof makeUser>; // [string, string]

type R = ReturnType<typeof makeUser>; // { readonly id: string; readonly name: string }

Behavior/output: Types stay aligned with the function signature.

Common mistake: Using these with overloaded functions and expecting perfect precision.

What is Awaited<T>?

Short answer: It unwraps nested Promise-like types into the resolved value type.

Deeper explanation: It’s useful in async helper types and prevents you from hand-rolling incomplete Promise unwrapping logic.

type A = Awaited<Promise<number>>; // number

type B = Awaited<Promise<Promise<string>>>; // string

Behavior/output: Compile-time unwrapping only.

Common mistake: Re-implementing it and missing edge cases.

How do you type this in a function?

Short answer: Add a fake first parameter this: Type to describe this inside the function.

Deeper explanation: This is useful for .call()/.apply() patterns or older-style method passing. It’s type-only; it doesn’t change runtime args.

function inc(this: { count: number }, delta: number) {

this.count += delta;

}

const c = { count: 0 };

inc.call(c, 2);

console.log(c.count);

Behavior/output: Prints 2.

Common mistake: Thinking the this parameter is passed at runtime like a real argument.

Interfaces vs types (intermediate view): when do you pick which?

Short answer: Use interface for extendable object contracts; use type for unions/composition and advanced type logic.

Deeper explanation: Interfaces support declaration merging, which is useful for augmentation but risky if accidental. Types are more expressive and often the default for modern TS type modeling. The best answer is consistency + clarity for your team.

interface A { x: number }

interface A { y: number } // merges: A has x and y

type B = { x: number } & { y: number };

Behavior/output: Merge happens only in the type system.

Common mistake: Accidentally merging interfaces across files and creating confusing “where did this property come from?” moments.

Interview tip: For “type vs interface,” say one sentence about tradeoffs, then one sentence about team consistency.

What is declaration merging?

Short answer: Multiple declarations of the same interface name combine into one type.

Deeper explanation: It’s used intentionally for augmentation and for improving library typings. It can also be a footgun in large repos if names collide.

interface Config { retries: number }

interface Config { mode: "dev" | "prod" }

const c: Config = { retries: 3, mode: "dev" };

console.log(c.mode);

Behavior/output: Prints dev.

Common mistake: Assuming interfaces don’t merge and being surprised by hidden properties.

What are namespaces, and why are they considered legacy?

Short answer: Namespaces are an older TS grouping pattern; modern code uses ES modules instead.

Deeper explanation: You’ll still see namespaces in older codebases and some .d.ts contexts. Today, import/export is the standard for organization and tooling compatibility.

namespace MathEx {

export const pi = 3.14159;

}

console.log(MathEx.pi);

Behavior/output: Prints 3.14159 (emission depends on module settings).

Common mistake: Mixing namespaces with modules and creating confusing dual patterns.

Class basics: what do public, private, and protected mean?

Short answer: They control visibility of class members (mostly at compile time).

Deeper explanation: public is default. private restricts access to the class. protected allows access in subclasses. For true runtime privacy, prefer #private fields (next question).

class A {

private x = 1;

protected y = 2;

getX() { return this.x; }

}

console.log(new A().getX());

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Assuming TS private is runtime-enforced (it’s not).

What are #private fields?

Short answer: #private fields are real JavaScript private fields enforced at runtime.

Deeper explanation: This is stronger than TS private. If you need actual encapsulation guarantees, # is the tool.

class Counter {

#n = 0;

inc() { this.#n++; }

get() { return this.#n; }

}

const c = new Counter();

c.inc();

console.log(c.get());

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Using private when you require runtime privacy guarantees.

What does implements do?

Short answer: It checks at compile time that a class matches an interface shape.

Deeper explanation: It doesn’t add runtime behavior. It’s a contract check: “my class has these members.” Great for plugin-style designs and long-lived APIs.

interface Serializer { serialize(): string }

class JsonSerializer implements Serializer {

serialize() { return "{}"; }

}

console.log(new JsonSerializer().serialize());

Behavior/output: Prints {}.

Common mistake: Believing implements enforces runtime checks (it doesn’t).

Interview tip: When classes show up, mention “compile-time vs runtime privacy” (

privatevs#private)-it’s a clean differentiator.

What is an abstract class?

Short answer: It’s a class you can’t instantiate directly; it can define shared implementation + abstract members.

Deeper explanation: Abstract classes are useful when you want partial implementation and a required contract for subclasses. If you only need a contract without implementation, interfaces are lighter.

abstract class Animal {

abstract sound(): string;

speak() { return `Says ${this.sound()}`; }

}

class Dog extends Animal {

sound() { return "woof"; }

}

console.log(new Dog().speak());

Behavior/output: Prints Says woof.

Common mistake: Using abstract classes just for typing when an interface would be simpler.

How do you type Promises and async/await?

Short answer: async functions return Promise<T>, and await gives you T.

Deeper explanation: Keep async return types explicit at module boundaries (public functions). Avoid Promise<any> leaks-use unknown and validate instead.

async function getNumber(): Promise<number> {

return 42;

}

getNumber().then(console.log);

Behavior/output: Prints 42.

Common mistake: Forgetting to await and treating a Promise as the resolved value.

How do you type catch errors safely?

Short answer: Treat catch (e) as unknown and narrow before using it.

Deeper explanation: Not everything thrown is an Error. People throw strings, numbers, or custom objects. Narrow with instanceof Error or convert to String(e) for logging.

try {

throw "oops";

} catch (e: unknown) {

const msg = e instanceof Error ? e.message : String(e);

console.log(msg);

}

Behavior/output: Prints oops.

Common mistake: Using e.message without narrowing.

What’s esModuleInterop doing conceptually?

Short answer: It aligns TS emit + type checking with how many devs actually import CommonJS modules.

Deeper explanation: If you’ve ever seen “default import is undefined,” this flag is often part of the fix (along with module settings). The key is consistency across the repo and matching runtime expectations.

export {};

Behavior/output: Placeholder-this is primarily config behavior.

Common mistake: Treating it as a “magic fix” without checking module format consistency.

What tooling do you typically see in TS projects (high-level)?

Short answer: tsc for type-check/build, ts-node for TS execution in dev, ESLint + typescript-eslint for linting, and Prettier for formatting.

Deeper explanation: You don’t need tutorials in interviews-just show you understand roles: tsc is the source of truth for type checking; lint catches style/bug patterns; formatting keeps diffs clean. In large repos, performance features like incremental builds and project references matter.

export {};

Behavior/output: Placeholder-tooling is about workflows, not runtime output.

Common mistake: Confusing ESLint type rules with the compiler’s type checking (compiler is the authority).

Interview tip: Tooling answers should be calm and practical: “compiler for types, lint for patterns, formatter for consistency.”

Advanced TypeScript interview questions and answers

Explain variance basics in generics (practical version)

Short answer: Variance describes how subtyping of T affects subtyping of Generic<T>, especially for producers vs consumers.

Deeper explanation: If something produces T (returns it), it tends to be covariant: Producer<Dog> can be used where Producer<Animal> is expected. If something consumes T (takes it as input), it tends to be contravariant-ish. You don’t need the math-just show you understand why some assignments are unsafe.

type Producer<T> = () => T;

type Animal = { name: string };

type Dog = Animal & { bark(): void };

const prodDog: Producer<Dog> = () => ({ name: "d", bark() {} });

const prodAnimal: Producer<Animal> = prodDog; // OK (returns a Dog which is an Animal)

console.log(prodAnimal().name);

Behavior/output: Prints d.

Common mistake: Assuming “generic types are always assignable” without considering input/output positions.

What is keyof and why is it powerful?

Short answer: keyof T gives you the union of property names of T.

Deeper explanation: keyof is how you write safe “property-based” utilities. When you pair it with generics and constraints, TS prevents invalid keys at compile time-no more stringly-typed property access.

function getProp<T, K extends keyof T>(obj: T, key: K): T[K] {

return obj[key];

}

const u = { id: "1", age: 30 };

console.log(getProp(u, "age"));

Behavior/output: Prints 30.

Common mistake: Typing key: string instead of K extends keyof T and losing safety.

What are indexed access types (T[K])?

Short answer: They give you the type of a property when you index a type by a key.

Deeper explanation: This is the type-level version of obj[key]. It’s how getProp returns the correct type, and how many utility types work under the hood.

type User = { id: string; age: number };

type Age = User["age"]; // number

const x: Age = 123;

console.log(x);

Behavior/output: Prints 123.

Common mistake: Forgetting that K must be constrained to keyof T to use T[K] safely.

What are mapped types?

Short answer: Mapped types transform properties of another type using [K in keyof T].

Deeper explanation: They’re like “for each property in T, do something.” This is how Partial, Readonly, and custom transforms are built. They’re incredibly useful-but keep them readable.

type ReadonlyMap<T> = { readonly [K in keyof T]: T[K] };

type User = { id: string; name: string };

type RUser = ReadonlyMap<User>;

const u: RUser = { id: "1", name: "Ada" };

console.log(u.id);

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Forgetting that mapped types preserve optionality unless you modify it.

What are conditional types?

Short answer: They choose a type based on a condition: T extends U ? X : Y.

Deeper explanation: Conditional types let you write type-level “if statements.” They’re essential for advanced utilities and type extraction. They also distribute over unions in some cases (next question).

type IsString<T> = T extends string ? true : false;

type A = IsString<"x">; // true

type B = IsString<number>; // false

Behavior/output: Compile-time only.

Common mistake: Treating conditional types like runtime logic (they’re purely compile-time).

Interview tip: Advanced answers land when you explain the why (“to keep APIs safe and ergonomic”), not just the syntax.

What is conditional type distribution over unions?

Short answer: If the checked type is a “naked” type param, conditional types distribute across union members.

Deeper explanation: T extends U ? X : Y with T = A | B becomes (A extends U ? X : Y) | (B extends U ? X : Y). To prevent distribution, wrap in a tuple: [T] extends [U] ? ....

type Dist<T> = T extends string ? "S" : "N";

type X = Dist<string | number>; // "S" | "N"

type NoDist<T> = [T] extends [string] ? "S" : "N";

type Y = NoDist<string | number>; // "N"

Behavior/output: X distributes; Y doesn’t.

Common mistake: Being surprised when a conditional type returns a union of results.

What does infer do in conditional types?

Short answer: infer lets you extract a type part into a new type variable.

Deeper explanation: This is type pattern-matching. It’s how you pull element types from arrays or return types from functions. Use it when you truly need it-many built-in utilities already cover common cases.

type Element<T> = T extends (infer U)[] ? U : T;

type A = Element<string[]>; // string

type B = Element<number>; // number

Behavior/output: Compile-time extraction.

Common mistake: Overusing infer when ReturnType/Parameters would be clearer.

What are template literal types?

Short answer: They build string literal types using template syntax at the type level.

Deeper explanation: Great for typed event names, routes, and key generation. They combine well with unions and string helper types like Capitalize.

type EventName = "click" | "hover";

type Handler = `on${Capitalize<EventName>}`; // "onClick" | "onHover"

const h: Handler = "onClick";

console.log(h);

Behavior/output: Prints onClick.

Common mistake: Creating overly complex string types that hurt readability and compile times.

satisfies vs type annotation: what’s the real win?

Short answer: satisfies validates shape while preserving inference; annotations can widen and lose literals.

Deeper explanation: If you annotate a config with : Config, you often lose literal keys/values that power keyof and discriminants. satisfies checks correctness without sacrificing inferred specificity.

type Cfg = { mode: "dev" | "prod"; retries: number };

const cfg = { mode: "dev", retries: 3 } satisfies Cfg;

console.log(cfg.mode);

Behavior/output: Prints dev.

Common mistake: Annotating and then wondering why keyof typeof cfg became too broad.

How do mapped type modifiers (+/- readonly, +/- ?) work?

Short answer: You can add/remove readonly or optional flags inside mapped types.

Deeper explanation: This is how you create “make everything required” or “make everything mutable” transformations. It’s powerful for internal helpers, but keep usage focused.

type Mutable<T> = { -readonly [K in keyof T]: T[K] };

type RequiredProps<T> = { [K in keyof T]-?: T[K] };

type U = { readonly id: string; name?: string };

type MU = Mutable<U>;

type RU = RequiredProps<U>;

export {};

Behavior/output: Compile-time transforms only.

Common mistake: Assuming these transforms also enforce runtime immutability (they don’t).

Interview tip: If you show an advanced type, narrate it like a story: “for each key… remove optional… preserve values…”

What is the asserts keyword used for?

Short answer: It creates assertion functions that narrow types after runtime checks.

Deeper explanation: This is a neat way to centralize validation logic. If the assertion passes, TS knows the type is narrowed; if it fails, you throw.

function assertString(x: unknown): asserts x is string {

if (typeof x !== "string") throw new Error("Expected string");

}

const v: unknown = "hi";

assertString(v);

console.log(v.toUpperCase());

Behavior/output: Prints HI.

Common mistake: Writing assertion functions that don’t actually validate (unsound).

How do you design a type-safe Result pattern?

Short answer: Use a discriminated union like { ok: true; value } | { ok: false; error }.

Deeper explanation: This makes error handling explicit and avoids “throw everywhere.” It also composes nicely with async flows and makes calling code honest: you must handle both paths.

type Result<T> = { ok: true; value: T } | { ok: false; error: string };

function safeDivide(a: number, b: number): Result<number> {

if (b === 0) return { ok: false, error: "Divide by zero" };

return { ok: true, value: a / b };

}

const r = safeDivide(10, 2);

console.log(r.ok ? r.value : r.error);

Behavior/output: Prints 5.

Common mistake: Using error: any and losing meaningful error structure.

How do you model “type-safe errors” in catch blocks?

Short answer: Keep catch as unknown, normalize to a known error shape, then return a Result.

Deeper explanation: This is a production-grade pattern: convert chaos at the boundary into a stable internal representation. It keeps business logic clean and type-safe.

type ErrorInfo = { message: string };

type Result<T> = { ok: true; value: T } | { ok: false; error: ErrorInfo };

function toErrorInfo(e: unknown): ErrorInfo {

return { message: e instanceof Error ? e.message : String(e) };

}

function run(): Result<number> {

try {

throw new Error("nope");

} catch (e: unknown) {

return { ok: false, error: toErrorInfo(e) };

}

}

const r = run();

console.log(r.ok ? r.value : r.error.message);

Behavior/output: Prints nope.

Common mistake: Assuming all thrown values are Error and accessing .message blindly.

What are declaration files (.d.ts) for third-party JS?

Short answer: They describe types for JS modules without providing runtime code.

Deeper explanation: If a library is written in JS, .d.ts files let TS users get typing. You can write ambient module declarations for untyped modules. The key: the declarations must match runtime behavior.

// example.d.ts (concept)

declare module "legacy-lib" {

export function ping(x: string): number;

}

export {};

Behavior/output: Enables type-checking for import { ping } from "legacy-lib".

Common mistake: Declaring APIs that don’t exist at runtime (types lie, runtime crashes).

What is module augmentation?

Short answer: It extends existing module types (like adding fields/methods to an interface exported by a module).

Deeper explanation: This is often used for plugins and customizing library typings. Use it carefully: it creates hidden coupling. Always ensure runtime behavior matches the augmented types.

declare module "./logger" {

export interface Logger {

trace(msg: string): void;

}

}

export {};

Behavior/output: Compile-time extension only.

Common mistake: Augmenting types without adding the runtime implementation.

Interview tip: For

.d.tsand augmentation, your golden phrase is: “types must reflect runtime truth.”

Global augmentation vs module augmentation: what’s the difference?

Short answer: Global augmentation extends global types; module augmentation extends a specific module’s types.

Deeper explanation: Global augmentation is for things like Window or global namespaces. Module augmentation is scoped to a module path. Keep both minimal and well-documented.

declare global {

interface Window {

__buildId: string;

}

}

export {};

Behavior/output: Type-only; doesn’t create window.__buildId at runtime.

Common mistake: Forgetting export {} and accidentally making declarations global when you didn’t mean to.

How does as const help with typed lookup tables?

Short answer: It preserves literal keys/values so TS can infer precise unions from data.

Deeper explanation: This is a super practical pattern: define your source of truth as data, and let TS derive types. It reduces duplication and keeps code honest.

const roles = ["admin", "user"] as const;

type Role = typeof roles[number];

const r: Role = "admin";

console.log(r);

Behavior/output: Prints admin.

Common mistake: Forgetting as const and ending up with string[] instead of "admin" | "user".

What are branded/opaque types and why use them?

Short answer: They prevent accidental mixing of identical-looking primitives (like two kinds of IDs).

Deeper explanation: Structural typing can allow mistakes like passing an OrderId where a UserId is expected. Branding makes them incompatible at compile time. It’s especially useful in large domains.

type Brand<T, B extends string> = T & { readonly __brand: B };

type UserId = Brand<string, "UserId">;

type OrderId = Brand<string, "OrderId">;

function asUserId(x: string): UserId { return x as UserId; }

const u = asUserId("u1");

// const o: OrderId = u; // error

console.log(u);

Behavior/output: Prints u1.

Common mistake: Thinking branding validates runtime data (it doesn’t).

What does noUncheckedIndexedAccess change in real code style?

Short answer: It nudges you to use guards/defaults for indexed access everywhere.

Deeper explanation: You’ll write more if (v == null) and ?? defaults, but you also ship fewer “undefined is not a function” bugs. It’s a trade you’ll usually take in production.

const map: Record<string, number> = { a: 1 };

const v = map["missing"]; // number | undefined (with the flag)

console.log(v ?? 0);

Behavior/output: Prints 0.

Common mistake: Overusing non-null assertions (!) to silence the new undefined warnings.

How do you keep advanced types from hurting compile performance?

Short answer: Prefer simpler types, avoid deep recursion, and don’t build type-level “machines” unless necessary.

Deeper explanation: Recursive conditional/mapped types can slow tsc and editors. Use named intermediate types, avoid giant unions, and keep public types straightforward. In big repos, type complexity is a real performance budget.

type Id = string;

type User = { id: Id; name: string };

export {};

Behavior/output: Simple types compile quickly.

Common mistake: Creating clever types that nobody can maintain (or that slow builds to a crawl).

Interview tip: Advanced interviews reward restraint: “I can do fancy types, but I optimize for clarity and build speed.”

When do overloads beat generics (and vice versa)?

Short answer: Overloads are great when return type depends on input shape; generics are great for preserving relationships across types.

Deeper explanation: If you have a few discrete cases, overloads are readable. If you’re writing a reusable helper that should work for many types, generics usually fit better.

function first(x: string[]): string;

function first(x: number[]): number;

function first(x: any[]) { return x[0]; }

console.log(first([1, 2, 3]));

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Using overloads when a single generic would be simpler (or vice versa).

What is satisfies great for in API design?

Short answer: Validating config objects while keeping keys and literals precise for derived types.

Deeper explanation: This lets you derive unions from config data confidently. It’s especially useful for registries and routing tables where keys matter.

type Handler = (input: string) => string;

const handlers = {

upper: (s: string) => s.toUpperCase(),

lower: (s: string) => s.toLowerCase(),

} satisfies Record<string, Handler>;

type HandlerName = keyof typeof handlers;

const name: HandlerName = "upper";

console.log(handlers[name]("Hi"));

Behavior/output: Prints HI.

Common mistake: Annotating handlers: Record<string, Handler> and losing literal key unions.

What are conditional utility types like Extract and Exclude?

Short answer: They filter union members: Exclude removes, Extract keeps.

Deeper explanation: They’re excellent for discriminated unions and selecting subsets. Use them when you need “only error cases” or “all non-error cases.”

type Status = "idle" | "loading" | "done" | "error";

type NonError = Exclude<Status, "error">;

const s: NonError = "done";

console.log(s);

Behavior/output: Prints done.

Common mistake: Expecting them to filter object properties (they filter union members).

What is NonNullable<T> and when should you use it?

Short answer: It removes null | undefined from a type-useful after validation.

Deeper explanation: It’s great for internal types where you know something is present. But don’t use it to wish away nulls-pair it with runtime checks that guarantee presence.

type Maybe = string | null | undefined;

type Yes = NonNullable<Maybe>; // string

const v: Yes = "ok";

console.log(v);

Behavior/output: Prints ok.

Common mistake: Using NonNullable without proving the value is non-null at runtime.

What do “advanced TypeScript interview questions” usually test?

Short answer: They test whether you can model real constraints safely while respecting runtime boundaries.

Deeper explanation: The “win” is not doing type wizardry; it’s designing APIs that are hard to misuse. Show you can combine narrowing, generics, conditional/mapped types, and runtime validation strategies. And show you care about readability and build performance.

function pluck<T, K extends keyof T>(arr: T[], key: K): T[K][] {

return arr.map(x => x[key]);

}

console.log(pluck([{ id: "a" }, { id: "b" }], "id"));

Behavior/output: Prints ["a","b"].

Common mistake: Writing types that are clever but impossible to explain clearly.

Interview tip: If you can explain it to a friend, you can explain it in an interview. Clarity beats cleverness.

Expert/Architect TypeScript interview questions and answers

How do you design type-safe boundaries for untrusted data?

Short answer: Treat external inputs as unknown, validate at runtime, then narrow into safe domain types.

Deeper explanation: This is the difference between “typed” and “safe.” The boundary is where bugs enter: JSON, env, files, network. Keep unknown at the edge, validate once, then pass typed values inward. This keeps the rest of your code clean and honest.

type User = { id: string; age: number };

function parseUser(x: unknown): User {

if (typeof x !== "object" || x === null) throw new Error("Not an object");

if (!("id" in x) || typeof (x as any).id !== "string") throw new Error("Bad id");

if (!("age" in x) || typeof (x as any).age !== "number") throw new Error("Bad age");

return x as User;

}

Behavior/output: Throws early on invalid input; returns a typed User on valid input.

Common mistake: Skipping runtime checks and trusting type assertions.

How do you scale TypeScript builds in large repos?

Short answer: Use incremental builds, project references, and clear package boundaries to reduce compile scope.

Deeper explanation: Big TS pain is “editor slow” and “CI slow.” Project references split compilation into smaller units and enable caching. Incremental builds reuse prior work. Also: keep dependency graphs sane and avoid giant “barrel” exports that trigger huge re-checks.

export {};

Behavior/output: Conceptual-this is about build structure, not runtime.

Common mistake: A single massive tsconfig for everything (slow builds, unclear boundaries).

What are TypeScript project references?

Short answer: They let you split a codebase into multiple TS projects with explicit dependencies and faster incremental builds.

Deeper explanation: Each package compiles independently and can emit .d.ts for dependents. This is the foundation of many monorepo setups.

export {};

Behavior/output: Conceptual-configured via tsconfig.json references.

Common mistake: Forgetting composite: true in referenced projects.

How do you handle mixed ESM/CJS module interop safely?

Short answer: Align module, moduleResolution, and runtime expectations; keep import styles consistent; use interop flags intentionally.

Deeper explanation: Module bugs are usually config mismatches disguised as “TypeScript issues.” Pick ESM or CJS per package and stick to it. Use type-only imports to avoid side-effect runtime imports. Test runtime behavior in the actual environment.

import * as fs from "node:fs";

console.log(typeof fs.readFile);

Behavior/output: Prints function.

Common mistake: Treating module interop as “just types” when it’s often a runtime format mismatch.

How do you publish and maintain .d.ts for a library?

Short answer: Emit declarations, keep the public API surface intentional, and avoid leaking internal implementation types.

Deeper explanation: Types are part of your public contract. Prefer stable exported types, and use Pick-style public DTOs rather than exporting internal shapes. Test your types like you test runtime code: with consumer examples.

export type PublicUser = { id: string; name: string };

Behavior/output: Consumers get stable typings.

Common mistake: Exporting internal types that change often and break downstream users.

Interview tip: Architect answers shine when you talk about boundaries: runtime data boundaries, package boundaries, and API boundaries.

How do you keep runtime and types aligned over time?

Short answer: Centralize validation, normalize errors, and avoid “typed lies” (as) in business logic.

Deeper explanation: Misalignment happens when runtime evolves but types don’t (or the other way around). Put parsing/validation in one place, return typed results, and keep the rest of your code free of unsafe casts.

function assertNonEmpty(s: unknown): asserts s is string {

if (typeof s !== "string" || s.trim() === "") throw new Error("Expected non-empty string");

}

Behavior/output: After passing, TS knows it’s a non-empty string (by convention).

Common mistake: Using asserts without a real check.

How do you design a type-safe plugin system?

Short answer: Use a stable core contract, typed registries, and literal keys preserved by satisfies.

Deeper explanation: Plugins should register capabilities under known keys. Avoid Record<string, any>. Use discriminated unions or mapped registries so plugin APIs are discoverable via autocomplete and checked by the compiler.

type Plugin = { name: string; init(): void };

const plugin = { name: "metrics", init() {} } satisfies Plugin;

console.log(plugin.name);

Behavior/output: Prints metrics.

Common mistake: Storing plugin data in untyped maps and losing all safety.

How do you standardize error handling across a TS codebase?

Short answer: Use a Result union or normalize exceptions into a shared error shape at boundaries.

Deeper explanation: Consistency prevents “sometimes string, sometimes Error, sometimes object.” A structured error type makes logging, retries, and user messaging reliable.

type ErrorInfo = { code: string; message: string };

type Result<T> = { ok: true; value: T } | { ok: false; error: ErrorInfo };

function fail(code: string, message: string): Result<never> {

return { ok: false, error: { code, message } };

}

console.log(fail("BAD_INPUT", "Missing id").ok);

Behavior/output: Prints false.

Common mistake: Throwing arbitrary things and forcing callers to guess shapes.

How do you keep compile times fast with advanced types?

Short answer: Limit recursive types, avoid huge unions, and keep public types simple.

Deeper explanation: Type-level complexity is a real performance cost. If editors lag, dev speed dies. Use intermediate type aliases, simplify conditional logic, and measure build performance after type-heavy changes.

type SafeString = string;

export {};

Behavior/output: Conceptual-simplicity helps the compiler.

Common mistake: Treating types as free-complex types can slow CI and editors.

How do you manage TS config consistency in a monorepo?

Short answer: Use a shared base tsconfig, enforce strictness consistently, and layer per-package overrides only when needed.

Deeper explanation: Consistency reduces “it compiles here but not there.” A base config (strict + module strategy) keeps expectations aligned. Package-level configs define boundaries and outputs (like .d.ts).

export {};

Behavior/output: Conceptual-config structure drives consistency.

Common mistake: Allowing each package to invent its own strictness rules.

Interview tip: At senior level, show you can make tradeoffs: safety vs speed, strictness vs migration reality.

How do you approach migrating a messy JS codebase to TS?

Short answer: Migrate incrementally, start at boundaries, prefer unknown over any, and turn on strictness step-by-step.

Deeper explanation: The fastest ROI is boundary safety: validate inputs and return typed outputs. Avoid “types everywhere” on day one-target the buggiest areas. Use noImplicitAny and strictNullChecks early if possible.

function parseEnv(v: unknown): string {

if (typeof v !== "string") throw new Error("Bad env");

return v;

}

Behavior/output: Throws early if env is invalid.

Common mistake: Using any as a migration crutch and never paying it back.

When do you choose runtime validation strategies?

Short answer: Always validate at trust boundaries; choose a consistent approach and apply it uniformly.

Deeper explanation: TS can’t validate runtime values for you. Whether you use hand-written guards or a validation layer, the key is consistency and coverage. Validate once, narrow once, and keep the rest of the code safe.

function isRecord(x: unknown): x is Record<string, unknown> {

return typeof x === "object" && x !== null;

}

console.log(isRecord({ a: 1 }));

Behavior/output: Prints true.

Common mistake: Validating partially (checking only top-level) then assuming nested data is safe.

How do you prevent accidental breaking changes in exported types?

Short answer: Treat types as API: be explicit about what you export and prefer additive changes.

Deeper explanation: Omit can unintentionally expose new fields later; Pick makes public surfaces intentional. Add fields as optional first when possible, and keep versioning discipline.

type V1 = { id: string; name: string };

type V2 = V1 & { email?: string };

export {};

Behavior/output: Additive evolution is safer for consumers.

Common mistake: Tightening types or removing fields without a major-version migration plan.

What’s your mental model for “types don’t exist at runtime” at scale?

Short answer: Use types to guide correct code, but enforce invariants with runtime checks at boundaries.

Deeper explanation: This keeps your system honest: types help you refactor safely, but runtime checks prevent bad data from entering. If you remember nothing else: “TS helps you write correct code; it doesn’t guarantee correct inputs.”

export {};

Behavior/output: Conceptual-this is about design discipline.

Common mistake: Using types as a substitute for validation in security- or money-related paths.

What’s one high-impact change you’d make to improve TS safety fast?

Short answer: Strengthen boundaries with unknown + validation and enable strict flags that reflect runtime reality (like strict nulls and unchecked indexed access).

Deeper explanation: This reduces the biggest sources of bugs first. Then you clean up any hotspots and unify module config. The result is a codebase that’s easier to maintain and harder to misuse.

function must<T>(v: T | null | undefined, msg: string): T {

if (v == null) throw new Error(msg);

return v;

}

console.log(must(1, "no").toFixed(0));

Behavior/output: Prints 1.

Common mistake: Trying to “perfect type” everything instead of fixing the highest-risk boundaries first.

Interview tip: Architect-level answers are about priorities: “biggest risk reduction first.”

TypeScript Coding Interview Practice (10 Tasks)

Task 1: groupBy (type-safe keys)

Problem: Group items by a key selector.

Constraints/expectations:

- Key must be

string | number | symbol - Preserve item type in grouped arrays

function groupBy<T, K extends PropertyKey>(items: readonly T[], keyFn: (item: T) => K): Record<K, T[]> {

const out = {} as Record<K, T[]>;

for (const item of items) {

const k = keyFn(item);

(out[k] ??= []).push(item);

}

return out;

}

const users = [

{ id: "u1", role: "admin" as const },

{ id: "u2", role: "user" as const },

{ id: "u3", role: "admin" as const },

];

const byRole = groupBy(users, u => u.role);

console.log(byRole.admin.map(u => u.id));

Explanation: PropertyKey keeps keys safe; Record<K, T[]> keeps values typed.

Example output: ["u1","u3"].

Task 2: once (preserve params + return)

Problem: Wrap a function so it runs once; later calls return the first result.

Constraints/expectations:

- Preserve parameter types and return type

- No

anyin the public wrapper signature

function once<F extends (...args: any[]) => any>(fn: F) {

let called = false;

let value: ReturnType<F>;

return (...args: Parameters<F>): ReturnType<F> => {

if (!called) {

called = true;

value = fn(...args);

}

return value!;

};

}

const init = once((x: number) => x * 2);

console.log(init(2));

console.log(init(99));

Explanation: Uses Parameters and ReturnType to keep the signature aligned.

Example output: 4 then 4.

Task 3: pluck (keyof + T[K])

Problem: Extract a property from each object in an array.

Constraints/expectations:

- Key must be valid for the object

- Return array must have the correct element type

function pluck<T, K extends keyof T>(items: readonly T[], key: K): T[K][] {

return items.map(i => i[key]);

}

console.log(pluck([{ id: "a" }, { id: "b" }], "id"));

Explanation: K extends keyof T prevents invalid keys; T[K] gives the right value type.

Example output: ["a","b"].

Task 4: assertNever (exhaustiveness helper)

Problem: Make a helper that guarantees exhaustiveness for unions.

Constraints/expectations:

- Accepts

never - Throws at runtime if reached

function assertNever(x: never): never {

throw new Error(`Unexpected: ${String(x)}`);

}

type Kind = { kind: "a"; x: number } | { kind: "b"; y: string };

function run(k: Kind) {

switch (k.kind) {

case "a": return k.x;

case "b": return k.y.length;

default: return assertNever(k);

}

}

console.log(run({ kind: "b", y: "hey" }));

Explanation: If you add a new kind, the compiler forces you to update the switch.

Example output: 3.

Task 5: Parse JSON safely (unknown + guard)

Problem: Parse JSON into { id: string; age: number } safely.

Constraints/expectations:

- Treat parsed data as

unknown - Validate with a type guard

type User = { id: string; age: number };

function isUser(x: unknown): x is User {

return (

typeof x === "object" && x !== null &&

"id" in x && typeof (x as any).id === "string" &&

"age" in x && typeof (x as any).age === "number"

);

}

function parseUserJson(json: string): User {

const x: unknown = JSON.parse(json);

if (!isUser(x)) throw new Error("Invalid user");

return x;

}

console.log(parseUserJson('{"id":"u1","age":30}').age);

Explanation: Boundary is unknown; the guard narrows to User.

Example output: 30.

Task 6: retry for async functions

Problem: Retry an async operation up to N times.

Constraints/expectations:

- Preserve return type

Promise<T> - Handle caught errors as

unknown

async function retry<T>(fn: () => Promise<T>, times: number): Promise<T> {

let last: unknown;

for (let i = 0; i < times; i++) {

try {

return await fn();

} catch (e: unknown) {

last = e;

}

}

const msg = last instanceof Error ? last.message : String(last);

throw new Error(`Retry failed: ${msg}`);

}

let attempts = 0;

retry(async () => {

attempts++;

if (attempts < 3) throw new Error("nope");

return "ok";

}, 5).then(console.log);

Explanation: Generic T keeps the async result type intact.

Example output: ok.

Task 7: Typed event emitter (minimal)

Problem: Build an emitter where event names control payload types.

Constraints/expectations:

onandemitare type-safe- Event map drives payload typing

type Events = {

data: { id: string };

error: { message: string };

};

class Emitter<E extends Record<string, any>> {

private handlers: { [K in keyof E]?: Array<(p: E[K]) => void> } = {};

on<K extends keyof E>(event: K, fn: (p: E[K]) => void) {

(this.handlers[event] ??= []).push(fn);

}

emit<K extends keyof E>(event: K, payload: E[K]) {

for (const fn of this.handlers[event] ?? []) fn(payload);

}

}

const em = new Emitter<Events>();

em.on("data", p => console.log(p.id));

em.emit("data", { id: "x" });

Explanation: keyof E and E[K] give you safe name-to-payload mapping.

Example output: x.

Task 8: deepFreeze type (deep readonly typing)

Problem: Return a deeply readonly type view (runtime can be shallow).

Constraints/expectations:

- Recursive deep readonly type

- Return typed readonly view

type DeepReadonly<T> =

T extends (...args: any[]) => any ? T :

T extends readonly (infer U)[] ? readonly DeepReadonly<U>[] :

T extends object ? { readonly [K in keyof T]: DeepReadonly<T[K]> } :

T;

function deepFreeze<T>(obj: T): DeepReadonly<T> {

return Object.freeze(obj) as DeepReadonly<T>;

}

const cfg = deepFreeze({ mode: "dev", nested: { retries: 3 } });

// cfg.nested.retries = 4; // compile error

console.log(cfg.nested.retries);

Explanation: The type enforces deep readonly usage even if runtime freeze is shallow here.

Example output: 3.

Task 9: makeMap from tuple entries (preserve literal keys)

Problem: Convert [["a", 1], ["b", 2]] as const into { a: 1, b: 2 } with typed keys.

Constraints/expectations:

- Input should be

as const - Output preserves literal keys

function makeMap<const T extends readonly (readonly [PropertyKey, any])[]>(entries: T) {

type Out = { [K in T[number] as K[0]]: Extract<T[number], readonly [K[0], any]>[1] };

const obj: any = {};

for (const [k, v] of entries) obj[k] = v;

return obj as Out;

}

const m = makeMap([

["a", 1],

["b", 2],

] as const);

console.log(m.a + m.b);

Explanation: Uses const generics + key remapping to keep literal keys.

Example output: 3.

Task 10: safeParseInt with Result

Problem: Parse an int without throwing; return a Result union.

Constraints/expectations:

- No exceptions for parse failures

- Typed error shape

type Result<T, E> = { ok: true; value: T } | { ok: false; error: E };